Illustration of Black Boy Likes to Draw

A Young Artist

Ezra Jack Keats was born on March 11, 1916. He was the third child of Benjamin Katz and Augusta "Gussie" Podgainy, Polish Jews who lived in East New York, which was then the Jewish quarter of Brooklyn. It was evident early on that the boy known as Jacob "Jack" Ezra Katz was an artistically gifted child.

The family was very poor. When 8-year-old Ezra was paid 25 cents to paint a sign for a local store, Benjamin began to hope that his son might be able to earn a living as a sign painter. But Ezra was in love with the fine arts. A good student who excelled in art, he was awarded a medal for drawing on graduating from Junior High School 149. The medal, though unimpressive-looking, meant a great deal to him, and Ezra kept it all his life. While at Thomas Jefferson High School, he won a national student contest run by the Scholastic Publishing Company for one of his oil paintings, depicting hobos warming themselves around a fire. That award also gave him much-needed encouragement.

This was during the Great Depression of the 1930s, a time when many, including the Katz family, suffered extreme hardship. Although Ezra's mother was supportive of his talent, his father wanted him to turn his hand to more practical skills. Working as a waiter at Pete's Coffee Shop in Greenwich Village, Benjamin Katz knew how hard earning a living could be. He worried that his son could never support himself as an artist. Despite his desire to discourage Ezra, Benjamin brought home tubes of paint, pretending that he had traded them with penniless artists for food. Ezra remembered his father saying, "If you don't think artists starve, well, let me tell you. One man came in and swapped me a tube of paint for a bowl of soup."

At his high school graduation, in January 1935, Ezra was to be awarded the senior class medal for excellence in art. Sadly, the day before, Benjamin died in the street of a heart attack. Ezra had to identify the body, and at this moment of loss he discovered his father's true feelings. In an interview with his friend the poet Lee Bennett Hopkins, he described the experience: "I found myself staring deep into his [my father's] secret feelings. There in his wallet were worn and tattered newspaper clippings of the notices of the awards I had won. My silent admirer and supplier, he had been torn between his dread of my leading a life of hardship and his real pride in my work."

Out in the World

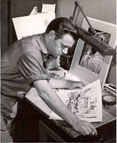

Unable to attend art school despite having received three scholarships, Ezra worked to help support his family and took art classes when he could. Among the jobs he held were mural painter with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and comic book illustrator, most notably at Fawcett Publications, illustrating backgrounds for the Captain Marvel comic strip.

Ezra went into the Army in 1943, and spent the remainder of World War II designing camouflage patterns. After the war, in 1947, he legally changed his name to Ezra Jack Keats, in reaction to the anti-Semitism of the time. It was his own experience of discrimination that deepened his sympathy and understanding for those who suffered similar hardships.

Ezra was determined to study painting in Europe, and in 1949 he spent one very productive season in Paris. Many of his French paintings were later exhibited in this country, and he continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. After returning to New York, he focused on earning a living as a commercial artist. His illustrations began to appear in publications such as Reader's Digest, the New York Times Book Review, Collier's and Playboy, and on the jackets of popular books. The Associated American Artists Gallery, in New York City, gave him two exhibitions, in 1950 and 1954.

One of his cover illustrations for a novel was on display in a Fifth Avenue bookstore, where it was spotted by the editorial director of Crowell Publishing, Elizabeth Riley. She asked him to work on children's books for her company, and published his first picture book in 1954. Jubilant for Sure, written by Elizabeth Hubbard Lansing, was set in the mountains of Kentucky, a long way from the Brooklyn streets or Paris ateliers. In an unpublished autobiography, Ezra marveled: "I didn't even ask to get into children's books." In the years that followed, Keats was hired to illustrate many children's books written by other authors, among them the Danny Dunn adventure series.

The Books

My Dog is Lost!, published in 1960, was Ezra's first attempt at writing his own children's book, co-authored with Pat Cherr. The main character is a boy named Juanito, newly arrived in New York City from Puerto Rico, who has lost his dog. Speaking only Spanish, Juanito searches the city and meets children from Chinatown, Little Italy and Harlem. From the beginning, Ezra cast minority children as his central characters.

Two years later, Ezra was invited to write and illustrate a book of his own. This was the first appearance of a little boy named Peter. Ezra's inspiration was a group of photographs he had clipped from Life magazine in 1940 depicting a little boy about to get an injection. "Then began an experience that turned my life around," he wrote, "working on a book with a black kid as hero. None of the manuscripts I'd been illustrating featured any black kids—except for token blacks in the background. My book would have him there simply because he should have been there all along. Years before I had cut from a magazine a strip of photos of a little black boy. I often put them on my studio walls before I'd begun to illustrate children's books. I just loved looking at him. This was the child who would be the hero of my book."

The book featuring Peter, The Snowy Day, was awarded the Caldecott Medal in 1963, the most distinguished honor available for illustrated children's literature at the time. (Ezra's Caldecott Acceptance Speech). Peter appears in six more books, growing from a small boy in The Snowy Day to adolescence in Pet Show!

The techniques that give The Snowy Day its unique look—collage with cutouts of patterned paper, fabric and oilcloth; homemade snowflake stamps; spatterings of India ink with a toothbrush—were methods Ezra had never used before. "I was like a child playing," he wrote of the creation process. "I was in a world with no rules." After years of illustrating books written by others, Peter had given Ezra a new voice of his own.

In subsequent books, he blended collage with gouache, an opaque watercolor mixed with a gum that produced an oil-like glaze. Marbled paper, acrylics and watercolor, pen and ink and even photographs were among his tools. The simplicity and directness of The Snowy Day gave way to more complex and painterly compositions.

In his evolution from fine artist to children's book illustrator, Ezra applied influences and techniques that had inspired him as a painter, from cubism to abstraction, within a cohesive, and often highly dramatic, narrative structure. His artwork also demonstrates an enormous emotional range, swinging from exuberant whimsy to deep desolation and back again.

Beyond Peter

After winning the Caldecott, Ezra found himself suddenly famous. During the 1960s and '70s, in addition to writing and illustrating his picture books, he taught illustration and traveled extensively. He visited classrooms around the country and corresponded with many children, exhorting them to "Keep on reading!"

The honors he received ran the gamut from prestigious to populist. On one end of the spectrum, in 1965 Ezra was the first artist invited to design a set of greeting cards for UNICEF, and in 1970 he was the first children's book author to be invited to donate his papers to Harvard University. On the other end, in 1974 a roller rink in Japan was named in his honor, and in 1979 Portland, Oregon, held a parade for him; Ezra happily attended both events.

By the time of Ezra's death following a heart attack in 1983, he had illustrated over 85 books, and written and illustrated 22 children's classics. He had just designed the sets for a musical version of The Trip, written by Stephen Schwartz and titled Captain Louie, which is still presented around the country and licensed for production by Musical Theatre International. He had designed a poster for The New Theatre of Brooklyn, and written and illustrated The Giant Turnip, a beloved folktale. Although Ezra never married or had a family of his own, he loved children, and was loved by them in return.

Illustration of Black Boy Likes to Draw

Source: https://www.ezra-jack-keats.org/ezras-life/

0 Response to "Illustration of Black Boy Likes to Draw"

Post a Comment